PRESCOTT, ARIZONA — What started as a simple archival task at the Prescott Territorial Heritage Museum has turned into one of the most stunning historical revelations of the century. A single, long-lost photograph—found buried in a trunk of dusty memorabilia—has challenged everything we thought we knew about the American frontier. It didn’t just rewrite Western folklore; it exposed a conspiracy buried for over a hundred years.

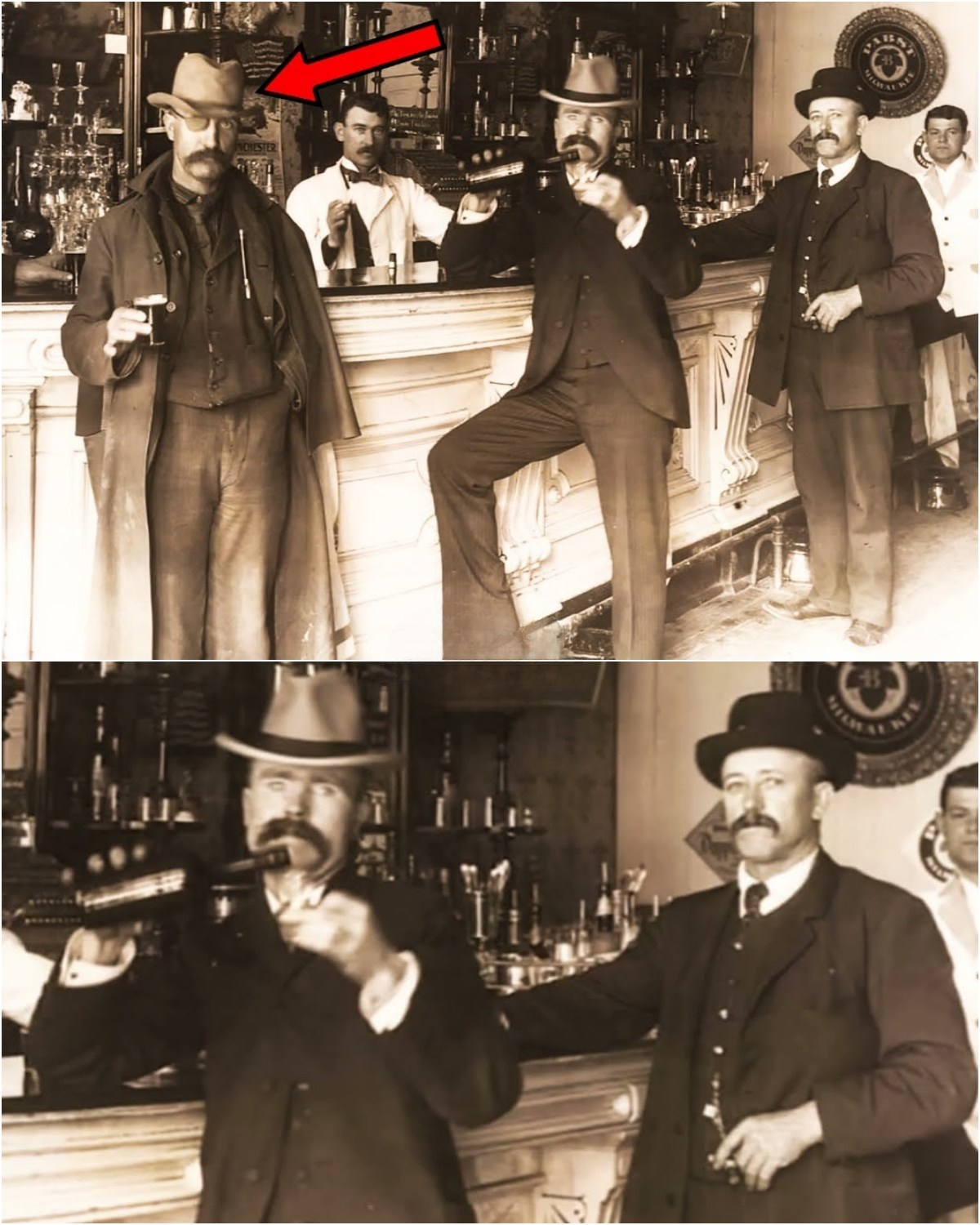

The photo, dated March 1886, was discovered in a bundle from the estate of Leland McGra, a deceased local cattle rancher. Initially, it looked like a standard Old West snapshot: cowboys in a saloon, laughing over drinks and cards. But when historians zoomed in on the image, they realized they weren’t just looking at any group of men—they were looking at legends and lies, side by side.

A Simple Day, an Unbelievable Discovery

Dr. Emily Hartwell, a respected historian from the University of Arizona, and her assistant Jonah Reyes were helping digitize items at the museum when they uncovered a sepia-toned photograph inside a wooden frame wrapped in oil cloth. The etched caption read, “Crystal Gulch Saloon, March 1886.”

As they scanned the image, something—or someone—caught their eye. Standing at the center was a man in a dark vest, hat tilted low, and a diagonal eye patch. Holding up a shot glass in mid-toast, he appeared eerily familiar. To both Hartwell and Reyes, there was no doubt: they were staring at One-Eyed Tom, the legendary and elusive leader of the Hollow Raven Gang.

Tom was long believed to be behind the deadly 1885 Gila Ridge train robbery, where six guards were killed and $70,000 in military payroll vanished. No confirmed photo of him had ever surfaced—until now.

But the real twist? He wasn’t alone.

Friends in High Places

Flanking One-Eyed Tom were two men wearing U.S. Marshal badges—William J. Cartwright and Emory Vance—both officially recorded as having died while pursuing Tom’s gang in the spring of 1886.

Yet here they were, not hunting Tom, but smiling and raising glasses with him.

This was no ambush, no chase. It was a gathering. A celebration. A cover-up.

Hartwell and Reyes discreetly uploaded the image to the museum’s secure archive and alerted a group of federal archivists and 19th-century law enforcement specialists. Within days, the name “One-Eyed Tom” resurfaced in internal government memos for the first time in over a century.

Shaking the Foundations

The fallout was immediate. Requests flooded in for sealed Pinkerton files and marshal dispatch logs. Within these documents, historians uncovered inconsistencies, missing records, and payment stubs linked to lawmen long presumed dead.

It was beginning to look like a coordinated betrayal. Facing poor wages, dangerous work, and political instability, it seemed that several frontier marshals cut secret deals with outlaw gangs—trading law and order for loot and survival.

And the missing $70,000? Still unaccounted for.

Until another clue emerged—from the photo itself.

A Map Hidden in Plain Sight

Lillian Mendoza, a graduate student enhancing the image for a digital exhibit, noticed faint carvings on the bar behind one of the men. When digitally enhanced and color-inverted, the marks revealed a crude map—a mountain range, a river, and an “X” near a formation known as Eliso in the Tumacacori Highlands near the Mexico border.

Next to the “X” were the words: “Raven end.”

Hartwell assembled a small, trusted team—including two federal agents—and launched a secretive expedition under the guise of a university research project. Using topographical overlays and historical surveys, they traced the location to an abandoned mine shaft labeled “Claim 27A.”

Inside, they found a rusted crate sealed with an 1880s railroad lock. Within were decomposing bonds marked “Department of the Treasury, 1885,” silver coins melted into clumps, and a revolver engraved with the initials “TM.”

Nearby, wrapped in oiled cloth and tucked into the stone, were skeletal remains. Alongside them: a weathered leather journal labeled “Property of Thomas M. Whitaker.”

They had found One-Eyed Tom—and his final confession.

The Journal That Changed Everything

Painstakingly restored, the journal was a mix of autobiography, strategic notes, and an explosive exposé.

Tom detailed his gang’s operations, implicating lawmen previously thought to be heroes. He wrote of the Gila Ridge robbery being coordinated with “Marshall D,” who gave them a timed window and escape route. This wasn’t a gang ambush—it was an inside job.

A chilling entry, dated days before the saloon photo, read:

“They’ll write songs about how he vanished, but they won’t know the truth. It was never about glory. It was about bleeding the system dry from the inside. That photo, that’s our last laugh. A room full of ghosts celebrating what the world couldn’t see.”

It confirmed what the photo had hinted at: the gang and the marshals had staged the entire pursuit. The train robbery. The deaths. The escape. All fabricated to protect reputations and divert attention.

History—Rewritten

The ramifications of this discovery are still unfolding. Government departments are quietly reevaluating long-accepted narratives. Academic institutions are revising their archives. Museum exhibits once honoring lawmen are now under review.

The Crystal Gulch Saloon photo has gone from being an obscure antique to a historical bombshell. It’s a stark reminder that the stories we inherit are often curated—and sometimes, completely false.

In the end, the Wild West wasn’t just a battleground between good and evil. Sometimes, it was a handshake in the dark between both.